The short version: sometimes they are the same person.

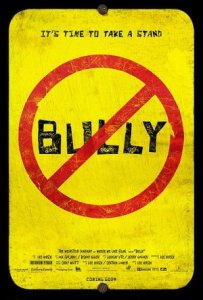

Growing up, especially in middle school, I was bullied quite a bit. Bullying is a serious thing. I still remember the names I was called and the faces who said them. I recall vividly having to restrain myself from retaliation. The kind of overt bullying I experienced is all-too-common for young people in America, and this was before social media. Now, home is not necessarily a haven, as bullying can continue on Facebook, Instagram, and other platforms. Young people are bullied for a variety of reasons: for looking different, for being attracted to someone of the same gender, for their poverty, or for a disability. 24/7 bullying culture is a serious matter. Victims of bullying are at an increased likelihood of mental and emotional problems, including temptations to suicide.

Victims deserve our sincere support and empathy. Christians in particular are called to love the marginalized, outcast, and oppressed. Psalm 34:18 reminds us that God is committed to the cause of all those who are victimized: “The Lord is near the brokenhearted, and saved those crushed in spirit.” Christians and other citizens who wish to care for the “least of these” simply cannot avoid concern for victims of physical, verbal, or other forms of violence. Many decent people are quick to come to the defense of victims.

For that reason, some unhealthy personalities will always seek to take advantage of others’ good nature and feign victim status in order to garner attention or gain power. KickBully.com offers excellent resources for addresses bullying. On a page dedicated to bullies who claim to be victims, they describe the behavior under three headings:

| A bully exaggerates the impact of your actions on him |

| – He exaggerates his pain and suffering

– He makes you feel guilty for causing his pain – He claims you don’t appreciate him |

| A bully focuses on past and future victimization |

| – He frequently reminds you of your past actions that hurt him

– He replays his pain whenever he wants to manipulate you – He brings up his pain long after the event occurred – He doesn’t seem to get over things – He says you will hurt him again if you don’t do what he wants |

| A bully uses his victimization to avoid changing his behavior |

| – He says you must earn back his trust, good will, friendship, support

– He claims his belligerence results from his being treated unfairly – He becomes angry and indignant when you try to reason with him – He says he is tired of doing all the compromising – He says he isn’t going to be so polite in the future – He suggests that others are ganging up on him |

They sum up this phenomenon by describing the behavior simply, “A bully pretends to be a victim in order to manipulate others. Because most people are good and compassionate, this is bullying at its worst. ”

Tim Field of BullyOnline.org attributes this behavior to a “manipulator,” one of a variety of attention-seeking pathological personality types who

“…[m]ay exploit family, workplace or social club relationships, manipulating others with guilt and distorting perceptions. While there may be no physical harm involved, people are affected with emotional injury…A common attention-seeking ploy is to claim he or she is being persecuted, victimized, excluded, isolated or ignored by another family member or group, perhaps insisting she is the target of a campaign of exclusion or harassment.”

We live at a moment in the modern West where we may begin to see more of this kind of behavior; an insightful new Atlantic piece names a subtle shift starting to take place in our culture that will profoundly impact how we relate to one another. Pre-modern cultures were largely honor cultures, where disputes would often be settled physically (a fight, or a duel), and requesting aid from third parties would be anathema in the case of an offense. The 19th and 20th century, particularly in the West, has seen a shift to a “dignity culture,” where insults were seen as less of an affront to personal honor and people are more likely to handle conflicts directly or simply ignore them. In a dignity culture, people are not totally averse to third party aid, but it is seen as a last resort to be avoided if possible. But now we are transitioning to a new kind of culture, described by sociologists thus:

The culture on display on many college and university campuses, by way of contrast, is “characterized by concern with status and sensitivity to slight combined with a heavy reliance on third parties. People are intolerant of insults, even if unintentional, and react by bringing them to the attention of authorities or to the public at large. Domination is the main form of deviance, and victimization a way of attracting sympathy, so rather than emphasize either their strength or inner worth, the aggrieved emphasize their oppression and social marginalization.”

It is, they say, “a victimhood culture.”

This victimhood culture clashes with the older dignity culture; slights that would be dismissed or handled reasonably in a dignity culture become fodder for great offense and shame campaigns by those influenced by the culture of victimhood. This is one aspect of the “suicide of thought” which we’ve examined previously. The sociologists quoted by The Atlantic piece elaborate:

“People increasingly demand help from others, and advertise their oppression as evidence that they deserve respect and assistance. Thus we might call this moral culture a culture of victimhood … the moral status of the victim, at its nadir in honor cultures, has risen to new heights.”

This helps to explain why we might see a rise in bullies playing the victim. As the culture shifts – and we are already seeing this in places like college campuses – there is more and more incentive to claim victim status, whether based on legitimate experiences or not. A good example of this kind of dynamic is the #CancelColbert faux controversy, in which a failed attempt was made to silence a comedian (who hadn’t made the offending tweet) for satirizing racism – which is a form of critique! Sound inane? It was, and the inanity was nicely summed up in this hilarious interview (not to mention Colbert’s mic-drop-worthy response).

The question The Atlantic does not answer, and that I find vexing, is the obvious one: what to do? The nature of claiming victimhood status is that it demands immediate deference; to question it is to risk nebulous but severe charges like insensitivity, harm, and blaming the victim. Moreover, bullying manipulators can easily turn any criticism or question to further the pretense of victimhood (as the chart above indicates).

The best option may just be to ignore them altogether; by challenging them directly you will likely feed their delusion and simply get roped into their histrionics. As with other kinds of toxic people, the only way to win with faux victims-turned-bullies is to minimize your exposure to them. Henry Cloud has some excellent thoughts along these lines in this lecture.

In a world that is far from the promised Kingdom, there will be victims and, sadly, those who pretend victimhood to further their own selfish ends. We must care deeply for the former while being wary of the latter. Or, as Jesus put it, we are called to be “as wise as serpents and innocent as doves.” (Matt. 10:16b, NRSV)

Have you experienced what sociologists are calling “victimhood culture?” Are there positive aspects to this culture? Are there other helpful ways to deal with it? Leave a comment below!