Courtesy UMNS

Courtesy UMNS

So then, whoever eats the bread or drinks the cup of the Lord in an unworthy manner will be guilty of sinning against the body and blood of the Lord. Everyone ought to examine themselves before they eat of the bread and drink from the cup. For those who eat and drink without discerning the body of Christ eat and drink judgment on themselves. (1 Corinthians 11:27-29)

The matter of unworthiness has a sticky history in Protestantism. Most astute readers of Scripture now agree that Paul’s concern for “eating unto damnation” was not an issue of individual sin, but rather of communal brokenness that made a mockery of the Lord’s Supper. At issue in Corinth was not a bunch of sinners eating something that they had no business eating (for we are always sinners asking for scraps and sips of grace), but that the community was unmaking the Body of Christ by scandalous practices: ignoring the hungry, getting drunk before the holy meal, etc. I have been reflecting on these passages as I wonder about one particular act at General Conference: the use of Communion as an act of protest.

A couple of quick notes: I am not a liturgical scholar, just a pastor who is interested in improving the celebration (both qualitative and quantitative) of the Eucharist my church. My chief issue is with the context of the Communion and not the particular motivations of those who went to the table that day (read: I would find it just as problematic if another caucus, say Good News or either side of the Israel/Palestine debate had taken similar action). Lastly, in the interest of fairness, I have invited Rev. Becca Clark, the elder who presided at this action, to share her perspective and respond if she so desires. I am a big believer – and General Conference illustrated this too well – that a major drawback of social media is the ability to snipe one another at a distance. I have given Becca a head’s up so that this might be a more civil dialogue, and she kindly granted me permission to share some of her thoughts as part of this initial post. A video of the events in question can be found here. (The video comes from the YouTube channel of the IRD, but rest assured that this is not an endorsement.)

Eucharist As An Act of Protest

From her own blog, here is Rev. Clark’s recollection. After the Conference rejected several petitions, including an “agree to disagree” statement led by Adam Hamilton and Mike Slaughter and enduring some inflammatory rhetoric

… we did the only thing we could do.

We set the communion table in the center of the room. We welcomed the visitors and supporters from outside the voting bar and delegates from the floor. We blessed bread and cup. I was the elder closest to the bread, and I lifted it in the air, breaking it as we are broken. I looked across the table and through my tears I saw my new friend and fellow laborer for justice, Gregory Gross, holding the cup.

We sent servers with (gluten free) wafers and cups of juice to serve those around the room. Some bystanders received communion with from those with whom they disagree, and some refused. I served those around me, offering them the Body of Christ as we all wept.

We stayed at the table when the session attempted to reconvene. Unable to get the delegates back to their seats and the visitors off the floor– indeed unable to even to get people to stop singing, the Bishop had no choice but to call for an early lunch.

In our correspondence, Rev. Clark indicated that the group had discussed the possibility of this being viewed as an unseemly act:

We discussed the use of the sacrament and the dangers of being perceived as politicizing a sacred gift. We also talked about maybe an affirmation of baptism instead. But what we decided was that the moment, no matter how the vote went, would be one of brokenness and deep pain for roughly half the room no matter what. And yet, in this brokenness and division, we are still one, and we still believe that God is able to bring healing, indeed salvation, out of the deepest pain and division.

A fundamental question seems to be, was this an act of unity or disunity? Was this a kind of prophetic sign-act, calling the assembly to a unity that was not yet a reality, or did it drive that wedge deeper? According to Rev. Clark, their thinking was that the Eucharist

was one standout example of what it means, theologically and spiritually, to live in the broken but believe in the whole and hope for the future we cannot see. Was there ever greater brokenness than the division, distrust, and ungodliness that led to Christ’s sacrifice? Is there any better example of how the broken becomes whole than the bread shared, the cup poured out to make us one?

To be sure, the Eucharist is a prophetic act, a sacrament that looks forward to God’s full reign of peace, justice, and love. We learn much about how to live the truly human life, the grace-enabled life of holiness, at God’s Table. Thus, the Eucharistic celebration is always an act of protest against brokenness, evil, and injustice in whatever forms.

But what about “Make us one?”

Paul seems clear that the brokenness of the community makes a mockery of the Lord’s Table. It is one thing for a Chinese house-church to break bread and share the cup in the midst of their persecution, as a remembrance of Christ’s sacrifice and anticipation of the New Creation against all the facts of their present situation. That is a truly sacramental, Christ-centered protest. Likewise, Oscar Romero lifting up the chalice in the midst of his enemies, knowing the danger he faced to bring God’s justice to his beloved El Salvador, was an act of protest. He died protesting, a martyr at the Table.

It is an altogether different kind of act if it is undertaken in such a way as to highlight a division in Christ’s Body, to drive the wedge deeper, to coerce and manipulate. This is precisely where this action became problematic. Communion is always to be an act of and with the whole assembly. In our recently approved study of the sacrament, This Holy Mystery, we find this guiding principle:

The whole assembly actively celebrates Holy Communion. All who are baptized into the body of Christ Jesus become servants and ministers within that body, which is the church…The one Body, drawn together by the one Spirit, is fully realized when all its many parts eat together in love and offer their lives in service at the Table of the Lord. (19)

Communion is the sacred meal that is at the heart of the life of the church. Because it is Christ’s Table, it unites us as few other practices can. As we share a loaf and cup, we are reminded that though we are many, we are indeed one through Christ Jesus. I think, for instance, that it would have been entirely appropriate for the presiding Bishop to call for bread and cup and offer the Eucharist as a means to call us back to our center. Something like this would have accomplished what I believe this group intended. What actually occurred, though, was the interruption of perhaps the most important gathering of the world-wide church so that a particular caucus could make a statement in the form of a sacrament. It seems to me that, however good the intention, the use of Communion at the height of a very heated debate made a Christ-centered act something much less. The whole assembly may have been welcome, but those at the table had taken it by force, making Christ’s Table effectively their table. In this, the witness of the Eucharistic table was sullied. Again, from This Holy Mystery:

Communing with others in our congregations is a sign of community and mutual love between Christians throughout the church universal. The church must offer to the world a model of genuine community grounded in God’s deep love for every person. (35)

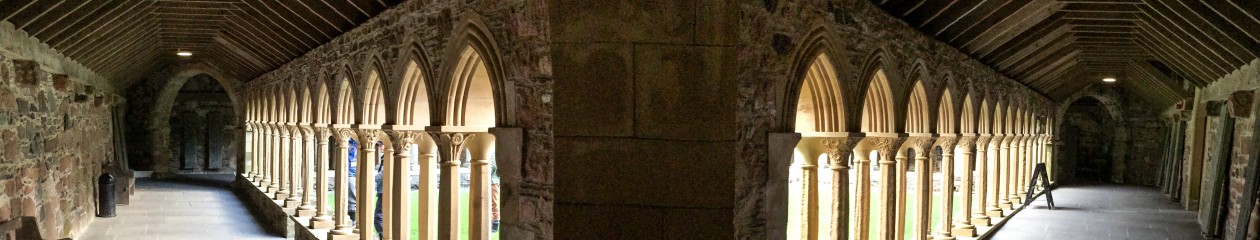

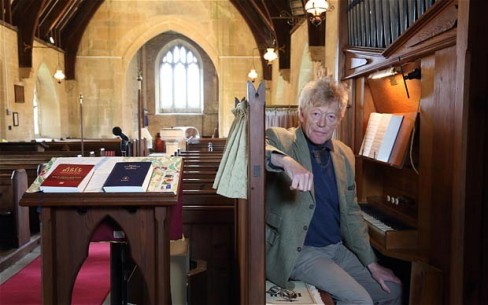

Celebrated well, the Eucharist accomplishes this. At the Table, we see the world as it should be: all are welcome, all are invited to acknowledge the good news of Jesus Christ, the Word made flesh, and to feast of his holy body and thus be made into his likeness. At General Conference on May 3, what should have been a liminal space, a “thin place” in the language of Celtic Christianity, became little more than another booth for another cause in the exhibition hall. Genuine community, already stretched, became less possible by this act. Mutual love was not encouraged.

The Missing Peace

I asked Rev. Clark for details of the liturgy that was used as they occupied the center table:

I was a delegate, so what I knew was get to the communion table. Someone will bring bread and juice. The ordained elder closest to the bread– which ended up being me– was to take the bread, silently pray words of blessing and institution, and break it. The rest just happened. By the time I was holding the bread, people were singing “let us break bread together.” the man who lifted the cup is a deacon and we had served on committee together, so it was a blessing to see him across the table. I prayed as best I could what I remembered of the communion liturgy, which I have memorized, but that day felt like– pour out your Spirit on us. We’re broken too and we want to be one body, like the bread makes us one. One with you and Christ. One with each other some day. Broken as we are, let us be your body for the world.

Many people served out of napkins of wafers and cups of juice. When I offered bread to those near me, I said, “the Body of Christ, broken as we are broken.”

Perhaps the greatest problem was all of this is that it was not a reconciled community that celebrated. Because this was an act of a few and not the whole, there was no opportunity for the whole assembly to go to the table forgiven and reconciled. In the UM Book of Worship, the following suggestions are given under “An Order of Sunday Worship”:

The people may offer one another signs of reconciliation and love, particularly when Holy Communion is celebrated. The Peace is an act of reconciliation and blessing, based on New Testament Christian practice…it is not simply our peace but the peace of Christ that we offer. (p. 26)

Again, this particular debate would have been a perfect occasion to ask the assembly to pass the peace. But because this was forced on the assembly by a few, no reconciliation was possible. In fact, the ability to join hands, listen to each other, or even “agree to disagree” was damaged, not helped, by this act.

Rev. Clark acknowledges that not all will approve:

I recognize it was not an action everyone can stand behind. However, my intent was to be pastoral in a moment of brokenness and call us to the reminder of the “reason for the hope that we have” that God can and will make us whole.

The fact that I cannot stand behind this matters little, to be honest. Our leaders seem much more concerned with institutional survival than sacramental faithfulness. And yet, I felt this warranted comment. In all the Twitter chat and Facebook rants, the voluminous articles and conversations about General Conference, I found it astounding that no one raised this particular question. For a church that claims John Wesley as its founding father, an Anglican priest who loved the Lord’s Table and went to great pains to encourage his people to celebrate it regularly and properly, this is a sad commentary indeed. In a world of partisan politics, bitter divides, and thoughtless polemic, the Eucharist should be one place where God reaches through all of the muck and mire to speak a word of grace and peace. The Lord’s Table is where, like Christ, we are taken, blessed, broken, and given. To make the Eucharist our act instead of God’s, a mere tool in a game of political manipulation rather than a sacrament of God’s grace, is a great disservice to Christ and his church. The words of Brian Wren remind us what can and should happen in this holy mystery:

As Christ breaks bread and bids us share,

each proud division ends.

The love that made us makes us one,

and strangers now are friends.

Sadly, this particular time at the Table exacerbated each and every “proud division.” Strangers became even more estranged. The body was not discerned.

Kýrie, eléison.

United Methodist Scholars for Christian Orthodoxy