“What I like best about being a Methodist is that you can believe anything you want.”

-Charles Wesley (via John Meunier)

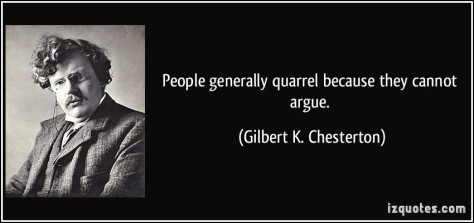

Creeds are a point of contention among Christians. Because we live in an age where authority is a dirty word, the idea that Christians should assent to any set of beliefs about God* is a scandal (dare I say – a heresy?). Even churches that do affirm the creeds, like the United Methodist Church, are sometimes wary about their liturgical and pedagogical use. An old article still (unfortunately) found on the UMC homepage actually claims, “Affirmations [like the creeds] help us come to our own understanding of the Christian faith.”

The last thing we as Christians need is “our own understanding of the Christian faith.” There is, after all, a deposit of faith that was revealed in Christ and taught by the apostles; this is what Jude refers to as “the faith once for all delivered to the saints.” (Jude 1:3)

Several folks I read to great benefit have been reflecting on creeds recently, and I commend their work to you. David Watson of United Seminary asks if the Wesleys were creedal. Joel Watts develops this, compiling an impressive list of quotations by Wesley on the creeds. Lastly, Andrew Thompson from Memphis Theological Seminary weighs in on Wesley and the creeds with a focus on the doctrine of the Trinity, including some quite helpful reflections on common misconceptions about the creeds and Methodist worship. Taylor Watson Burton-Edwards’ thoughtful feedback here and here on two of the above posts is also worth your attention.

Below is an excerpt from a letter that Wesley wrote to a Roman Catholic, attempting to find some common ground. Thompson, linked above, quotes this section in part, observing keenly, “Wesley resorts to a creedal form of writing.”

Ted Campbell once suggested this list “is as close as John Wesley came to a statement of essential fundamental teachings, even though it is not structured as a list of fundamental teachings.” While not a formal creed, it draws heavily on the structure and content of the Nicene Creed and Apostle’s Creed. More specifically, it bears commonality to the baptismal form of creeds (note the personal language of “I believe”). Campbell also notes that a certain Bishop Pearson – whom Watts quotes in the above link – contemporary with the Wesleys, had written a well-known exposition on the Apostle’s Creed, which may have influenced the whole Wesley clan (including Mama Sussanah, who herself wrote a commentary on the Apostle’s Creed). With all of this in mind, consider what I am happy to call, with only a bit of tongue-in-cheek, John Wesley’s Creed:

A true Protestant may express his belief in these, or the like words:

As I am assured that there is an infinite and independent Being, and that it is impossible there should be more than one, so I believe that the one God is the Father of all things, especially of angels and men; that he is in a peculiar manner the Father of those whom he regenerates by his Spirit, whom he adopts in his Son as co-heirs with him, and crowns with an eternal inheritance; but in a still higher sense the Father of his only Son, whom he hath begotten from eternity.

I believe this Father of all, not only to be able to do whatsoever pleaseth him, but also to have an eternal right of making what and when and how he pleaseth, and of possessing and disposing of all that he has made; and that he, of his own goodness, created heaven and earth and all that is therein.

I believe that Jesus of Nazareth was the Saviour of the world, the Messiah so long foretold; that, being anointed with the Holy Ghost, he was a prophet, revealing to us the whole will of God; that he was a priest, who gave himself a sacrifice for sin, and still makes intercession for transgressors; that he is a king, who has all power in heaven and in earth, and will reign till he has subdued all things to himself.

I believe he is the proper, natural Son of God, God of God, very God of very Gods and that he is the Lord of all, having absolute, supreme, universal dominion over all things; but more peculiarly our Lord, who believe in him, both by conquest, purchase, and voluntary obligation.

I believe that he was made man, joining the human nature with the divine in one person; being conceived by the singular operation of the Holy Ghost, and born of the blessed Virgin Mary, who, as well after as before she brought him forth, continued a pure and unspotted virgin.

I believe he suffered inexpressible pains both of body and soul, and at last death, even the death of the cross, at the time that Pontius Pilate governed Judaea under the Roman Emperor; that his body was then laid in the grave, and his soul went to the place of separate spirits; that the third day he rose again from the dead; that he ascended into heaven; where he remains in the midst of the throne of God, in the highest power and glory, as mediator till the end of the world, as God to all eternity; that in the end he will come down from heaven to judge every man according to his works, both those who shall be then alive and all who have died before that day.

I believe the infinite and eternal Spirit of God, equal with the Father and the Son, to be not only perfectly holy in himself but the immediate cause of all holiness in us; enlightening our understandings, rectifying our wills and affections, renewing our natures, uniting our persons to Christ, assuring us of the adoption of sons, leading us in our actions, purifying and sanctifying our souls and bodies, to a full and eternal enjoyment of God.

I believe that Christ by his apostles gathered unto himself a Church, to which he has continually added such as shall be saved; that this catholic (that is, universal) Church, extending to all nations and all ages, is holy in all its members, who have fellowship with God the Father, Son and Holy Ghost; that they have fellowship with the holy angels, who constantly minister to these heirs of salvation; and with all the living members of Christ on earth, as well as all who are departed in his faith and fear.

I believe God forgives all the sins of them that truly repent and unfeignly believe his holy gospel; and that at the last day all men shall rise again, every one with his own body. I believe that, as the unjust shall after their resurrection be tormented in hell for ever, so the just shall enjoy inconceivable happiness in the presence of God to all eternity.

Before you say, “It’s not what you believe, it’s what you do,” hold the phone. Wesley adds briefly after this list: “Does he practise accordingly? If he does not, we grant all his faith will not save him.” For Wesley, it is faith AND works, belief AND practice that make up the Christian life.

So, what do you make of John Wesley’s Creed? What holds up today as truths central to Christian belief? What doesn’t?

Thanks be to God that the Christian faith is not malleable based on our whims. The good news is this: I don’t have to grope in the darkness and come to my own understanding of God. God has come for me and to me long before I have ever sought out God. What is this God like? I have only to look in the back of the United Methodist Hymnal.

*Outside of believing that God is benignly benevolent and really wants me to be personally fulfilled on my own terms – AKA Moralistic Therapeutic Deism.